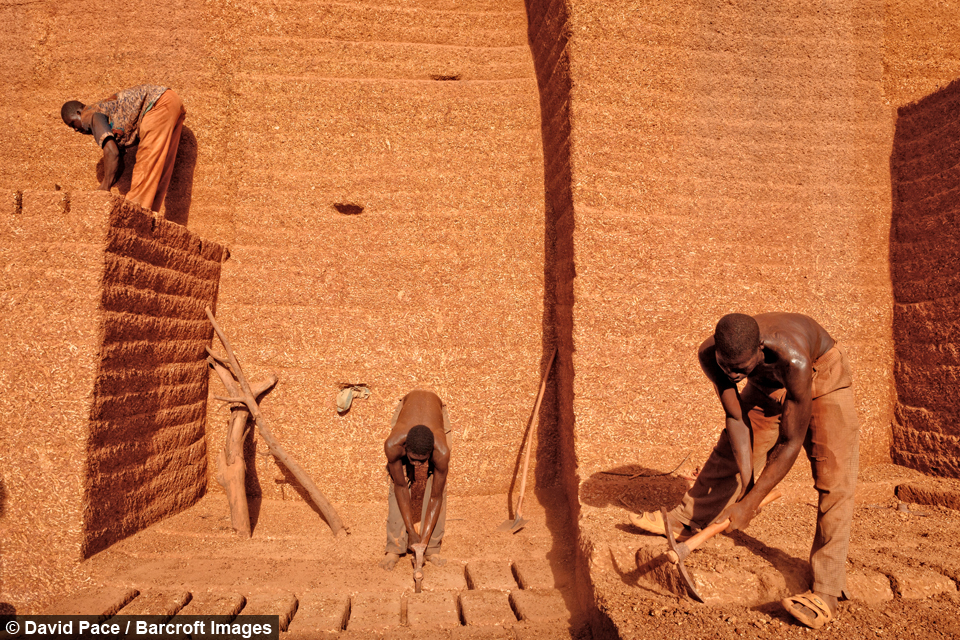

Workers endure 40C heat to build up to 100 bricks a day by hand

By Hannah Stevens @Hannahshewans

Scroll down for the full story

Between 2008 and 2016, photographer David Pace has documented the conditions of a remote brick quarry in the small African country of Burkina Faso.

The photographer was visiting the nearby village of Bereba, which has no electricity or running water, when he grew curious about where the bricks for the local houses originated from.

With the help of his good friend Dounko he gained access to the Karaba quarry to document the vast pit and the proud workers within.

David said: “It is always hot and dusty at the quarry. The average daily temperature is 35-40C.

“Cutting bricks from solid rock by hand, without any protection, and usually without shoes, is very difficult. The men who work there are in tremendous physical shape.

“The workers love to be photographed, both while they are working and when they are taking a break. They enjoy mugging for the camera.

“Every year when I return, I give them their portraits from the previous year. They are proud of the work that they do and they want it to be seen by others.”

The vast quarry continues to grow to accommodate the surrounding villages and David says the quarry has grown three to four times larger since his initial visit.

The 66-year-old photographer said: “It was not difficult to gain access to the quarry, finding it, however, was a challenge. It is located about 20 kilometres from Bereba and takes about 45 minutes to drive there along a rutted dirt road.

“The quarry is only a short distance from the road, but there are no landmarks or road signs. It is a deep pit, invisible from the road and obscured by the surrounding cornfields.

“I would never have found it without Dounko’s help. Dounko was also instrumental in helping to explain to the workmen my overarching project of photographing daily life in rural Burkina Faso.”

Gaining its independence in 1960, Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world, yet gold is one of its largest exports.

The California-based photographer added: “Each man works for himself and sells the bricks that he makes. An individual can make 50 to 100 bricks per day.

“Brick makers earn two to four times the average national income. Work usually begins around 9am in the morning and ends before sunset, between 5pm and 6pm in the evening.

“Bricks are made every day of the week, but not everyone is at the quarry every day. All of the workers are farmers as well as brick makers, so they sometimes take time off from brick making to tend the family farm.”

Over the years the quarry’s workforce has fluctuated and David saw as many as 60 workers in 2016 when there was a higher demand for bricks, while he saw as few as ten workers during his 2013 visit.

While venturing into the depths of the pit, David achieved his dream of becoming a photographer who disappears in plain view, allowing him to wander the quarry unhindered.

He said: “As a young street photographer in the US and Europe, I dreamed of being invisible. I wanted to photograph real life without influencing what was happening around me.

“When I came to West Africa I realised this was a ridiculous notion. I am almost always the only white man for kilometres around and it is impossible to conceal myself.

“I must interact with every person I photograph, explain my project completely and be willing to bring back a print when I return.

“I have become so familiar to the men in Karaba and so trusted by them that, in a sense, I disappear in plain view.

“I finally achieved the invisibility I once sought, but this new invisibility is achieved by becoming a part of the community.”