Tribal Revelry: Thousands gather for two day ceremony to transfer democratic power

By Hannah Stevens @Hannahshewans

Scroll down for the full story

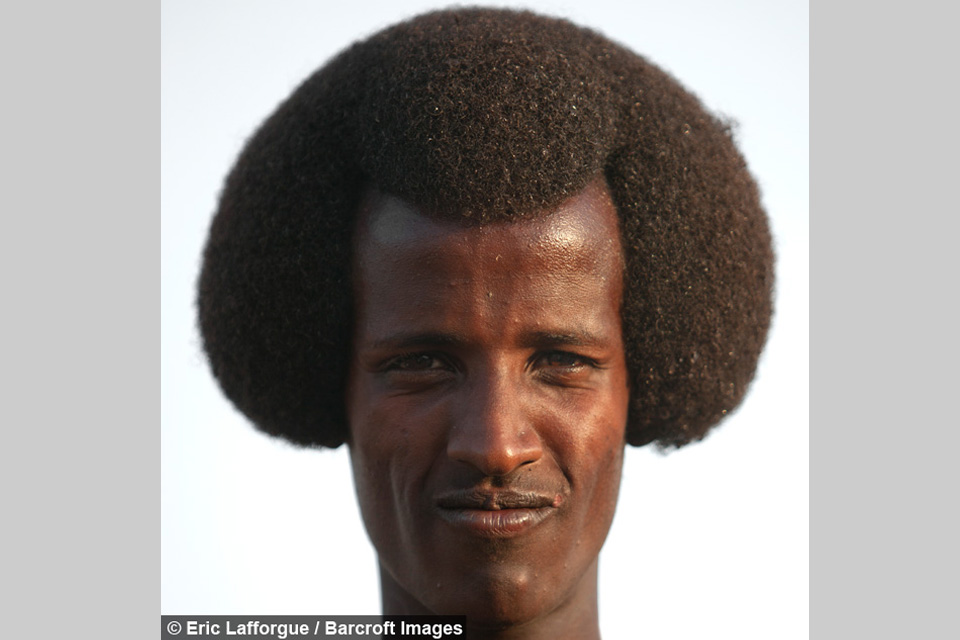

The Karrayyu have fiercely resisted the tourist industry and remain very protective of the Gadaa ceremony, which is held every eight years to elect a new Chief.

Foreigners rarely attend the two-day ceremony, but Eric Lafforgue was invited to attend after Roba – a tribesman now studying in Italy – spotted his photos of the tribe on Flickr.

Eric said: “I did not find any pictures from the event so I decided to go, even though I was fearing a touristic event.

“Once in the place it was not touristic at all - I was the only foreigner!

“There were thousands of people and nobody asked for money, or refused any picture! A dream in Ethiopia!

“They just want to live their life and not be disturbed. They have very ancient traditions and they do not want to see tourists come and change things with money.

“Many are also warriors and they see foreigners as possible dangers in the bush!”

In the Gadaa system individuals are split into five equal parties based on generation, age and their lineage, they then cycle through five eight-year long grades - each involving new responsibilities.

Gadaa also refers to the ruling grade; every eight years a new chief, called an Ababoku, is elected to lead the tribe with his party.

Before being permitted to attend the ceremony, Eric’s contact Roba had to negotiate his access with the tribe elders.

The elders let him attend so that he could raise awareness of their struggle with drought and border disputes with neighbouring Afar and Argoba tribes.

In preparation for the ceremony the Karrayyu build a venue constructed out of three concentric circles. The inner one houses stand-alone shelters for members and their families, the second keeps the cattle awaiting sacrificial slaughter and the third acts like a check-in station for a stadium.

Between each check-in point sits a rectangular cow dung barrier decorated with yellow fruit called hidi, symbolizing fertility and prosperity. Guests cannot cross until all the guests have arrived and the elders grant permission.

Then the revelry begins - with tribesman recording their sacred song on battered Nokia’s to preserve the tribes culture - followed by a host of politically charged poetry performed by Karrayyu men.

Afterwards a group of men depart to search for the current chief’s sister - who, as part of the ceremony, has hidden herself amongst the crowds.

Hours later a shout rings round and the chief’s sister returns singing a melodic ceremonial song and the women join in with improvised poetry.

Roba said: “They are singing about their brothers, praising them, appreciating them, encouraging them, saying, ‘Now you should be ready to pass power’.

“They are also singing for those who have died in the war. This is a song where people can cry.”

Revellers begin to cross the dung gates, following the family in charge of each entrance, and signaling the official start of the Gadaa ceremony.

A few hours later the first slaughter of the bulls begins and the slayer soaks his palms with blood before rubbing it into his forehead.

Hours of singing and dancing follows before the chanting circle reappears at midday, signalling the core part of the ceremony - the transfer of power.

Eric said: “The old one must put cow blood on his head and he was crying during it. It was very moving, even if the atmosphere was chaotic! He gives some herbs to the new one and the power then changes hands.

“Afterwards all the men sing and dance again! Nobody slept for the entire two days!”

When the chief has performed his sacrifice, members of his party follow suit and their sisters have their ears pierced with a single thorn of an agamsa, a tree resistant to drought that represents good luck.

To officially transfer power the old chief and his party elders lay handfuls of grass on the dung gates - a process known as ireefatuu - and the chief walks away, leaving the power in the hands of the new chief.

Following the exchange the members of the new party explode into celebration as they break off into chanting circles across the open plains.

Newcomers pray for peace, rain and good luck and the families prepare to build a new isolated village, where they will reside for their eight-year term.

Lafforgue hopes the Karrayyu will one day find a way to use tourism for monetary benefit without impacting their sacred traditions.

He said: “If they controlled the group of tourists then they can get money and raise awareness, as they are Oromos and they suffer a lot in Ethiopia at this time. They have spent a long time fighting the government.

“Their culture is very rich so they should maybe provide cultural tours, but not human safari tours like in Omo valley!”